|

A man with a kidney transplant presents with subacute diplopia |

- History of Present Illness

- A male in his sixties with a living-related kidney transplant more than a decade ago, complicated by diabetes and moderate chronic allograft nephropathy, presented with a 2-week history of intermittent diplopia, nausea and vomiting. Upon further questioning, he described a subacute history of disequilibrium and forgetfulness.

- Past Medical History

Hypertension.

Kidney failure of unknown etiology.

Living-related kidney transplant.

Post-transplant diabetes mellitus.

Chronic allograft nephropathy, Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and IgA nephropathy.

- Medications

- Aspirin, atorvastatin, metoprolol, hydrochlorothiazide, insulin, pioglitazone, mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg twice a day, and tacrolimus 2 mg twice a day.

- Epidemiological History

- No history of tobacco, illicit drugs or alcohol abuse. No contact with pets.

Born in Mexico, migrated to US >20 years before. No recent travel history.

Previous laborer but retired for over 2 years.

- Physical Examination

- The patient appeared ill. The blood pressure was 163/83 mmHg, heart rate 84 beats per minute, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, pulse oximetry 99% on room air and temperature 98.1°F (36.7°C). Eye exam revealed right-sided internuclear ophthalmoparesis (INO) as evidenced by right medial rectus palsy and abducting nystagmus on the left eye, without ptosis, anisocoria or papilledema. He had bilateral patellar hyperreflexia and ankle clonus. The rest of examination was normal.

- Studies

Initial laboratory tests showed creatinine of 3.3 mg/dL (reference range (RR) 0.6-1.4) (increased from a baseline of 2.7 mg/dL 1 year before), urea 28 mg/dL (RR 8-20), hemoglobin 9.7 mg/dL (RR 12.9-16.8). The rest of routine laboratory findings, including HIV and syphilis screening and serum tacrolimus levels were within normal reference ranges.

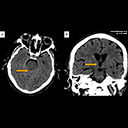

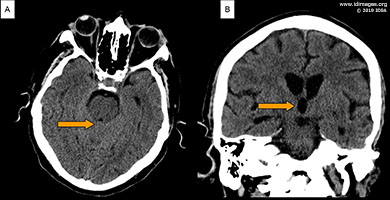

Computed tomography (CT) of the head (Figure 1A and B) and chest demonstrated obstructive hydrocephalus with tectum and midbrain edema and a 1.1 cm, noncalcified pulmonary nodule in the left lower lobe posteriorly (Figure 2).

- Figure 1A and B: Computed tomography of the head without contrast demonstrating obstructive hydrocephalus with tectum and midbrain edema

- Figure 2: Computed Tomography of the chest without contrast demonstrating a 1.1 cm solid noncalcified nodule in the left lower lobe posteriorly.

- Clinical Course Prior to Diagnosis

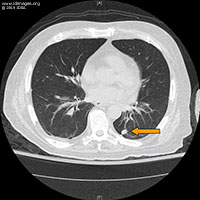

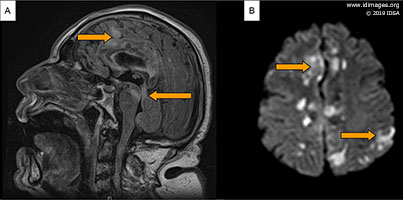

- The patient was admitted to the hospital and was scheduled for a Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the brain. On day 2 his neurological status rapidly deteriorated. He became acutely confused and obtunded requiring intubation for airway protection and transfer to the medical intensive care unit. His temperature increased to 100.4°F (38.0°C) and he was empirically started on vancomycin, meropenem and acyclovir. Infectious diseases service was consulted. Brain MRI showed diffusion restriction and corresponding high T2 and FLAIR signal involving the tectum and midline periaqueductal region of the midbrain and a small area of the medial superior left cerebral hemisphere; there was midbrain edema with associated stenosis of the aqueduct and obstructive hydrocephalus of the third and lateral ventricles (Figure 3A and B).

- Figure 3: MRI brain without contrast on day 3. (A) Sagittal FLAIR images showing area of hyperintensity in the tectum and midline pre-aqueductal region of the midbrain. Associated stenosis of the aqueduct with obstructive hydrocephalus. (B) Diffusion-weighted imaging showing high-signal areas in a small area of the medial superior left cerebral hemisphere. There was no definite corresponding apparent diffusion coefficient changes.

- Diagnostic Procedure(s) and Result(s)

Serum cryptococcal antigen was positive to 1:512 dilutions. Serum Cytomegalovirus (CMV) PCR showed a positive DNA of 1122 IU/mL (reference range < 200 IU/mL). An external ventricular drain (EVD) was placed revealing moderately increased intracranial pressure. CSF analysis showed clear fluid, glucose of 10 mg/dL (RR 50-70), protein of 23 mg/dL (RR 20-50), leukocytes of 1/µL (RR 0-5) and erythrocytes < 1/µL (RR 0-5). CSF cryptococcal antigen was positive 1:>8192 dilutions. Encapsulated yeasts were seen on India Ink staining. Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, HSV and CMV PCR were all negative on CSF. After 2 days of incubation, CSF culture revealed Cryptococcus neoformans growth.

- Treatment and Followup

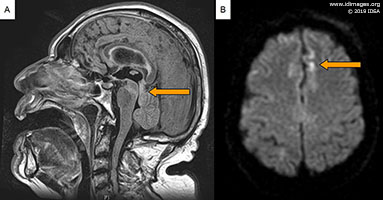

The patient was switched to intravenous liposomal amphotericin and flucytosine on day 3 after serum cryptococcal antigen showed positivity. Acyclovir was changed to ganciclovir given initial concern for CMV infection (later discontinued after CMV PCR was negative on CSF). The EVD was removed after 5 days, showing normal intracranial pressure. Subsequently, serial CT scans of the head were done which showed no progression of the hydrocephalus. Unfortunately, the patient’s neurological function continued to deteriorate. Repeat MRI of the brain after 14 days of treatment revealed findings consistent with multiple scattered ischemic lesions throughout both cerebral hemispheres, corpus callosum, deep white matter, subcortical white matter and cortex with involvement of dorsal midbrain (Figure 4a and b). He died shortly after.

- Figure 4: Follow up MRI brain without contrast at 14 days. (A) Sagittal FLAIR images showing scattered areas of hyperintensity in corpus callosum, deep white matter, subcortical white matter and cortex. (B) Diffusion-weighted imaging showing high-signal areas in both cerebral hemispheres and cortex. There was no definite corresponding apparent diffusion coefficient changes.

- Discussion

Cryptococcus infection is the third most common invasive fungal infection and the most common cause of central nervous system (CNS) fungal infection in solid organ transplant recipients (1,2). Kidney and liver transplant patients appear to have the highest risk compared to other solid organ transplants (3). The diagnosis of cryptococcal meningoencephalitis can be challenging as it commonly presents with a subacute onset and nonspecific symptoms and signs. Neuro-ophthalmologic dysfunction is common. Papilledema and cranial nerve (CN) III and VI involvement are the most frequent presentations (4); specific syndromes such as INO are very rare.

INO is one of the most discrete localizing signs in medicine and is usually of considerable value in predicting multiple sclerosis or stroke. Some reports have suggested higher frequency of other causes such as infection or trauma, reaching up to a quarter of all causes. Based on a 2005 review, up to 28% of all cases of INO are due to unusual causes. However, only 4% were associated with infections and even fewer with cryptococcal meningoencephalitis (5). Several theories have been postulated to explain the pathophysiology behind this finding. Cryptococci are thought to physically block CSF drainage across the arachnoid villi and subarachnoid spaces leading to increased intracranial pressure with compression of nerve structures and tracts. Inflammation and direct invasion of cranial nerves is also thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of cranial neuropathies (2,6). Unilateral INO due to involvement of the medial longitudinal fasciculus on one side of the pons is usually vascular or demyelinating in nature. Phlebitis and arteritis have been demonstrated in pathological examination of human brains infected with Cryptococcus (7). Reports of reversibility of the ocular findings with treatment supports the vasculitic nature of the phenomenon.

Amphotericin B (AmB) remains the cornerstone of therapy for cryptococcal meningitis. Liposomal preparations of AmB are preferred as first-line therapy in organ transplant recipients due to the frequency of reduced renal function in such patients (9). Flucytosine is recommended as adjunct therapy as the combination has shown reduced rates of treatment failures (10), and direct survival benefits have also been reported (11). Fluconazole maintenance therapy should be continued for at least 6-12 months. During the early treatment phase of cryptococcal meningitis, control of increased intracranial pressure with external drainage is critical (8), either by repeated lumbar punctures or by ventricular or lumbar drains. In conclusion, cryptococcal meningoencephalitis is a detrimental infection in solid organ transplant recipients and it should be suspected in patients with any combination of fever, headache and focal neurological signs.

- Final Diagnosis

- Cryptococcal meningoencephalitis.

- References

-

- Wald-Dickler N, Blodget E. Cryptococcal disease in the solid organ transplant setting: review of clinical aspects with a discussion of asymptomatic cryptococcal antigenemia. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2017 Aug;22(4):307-313.

PMID:28562416 (PubMed abstract)

- Liyanage DS, Pathberiya LP, Gooneratne IK, Caldera MH, Perera PW, Gamage R. Cryptococcal meningitis presenting with bilateral complete ophthalmoplegia: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2014 May 31;7:328.

PMID:24885277 (PubMed abstract)

- Pappas P, Alexander B, Andes D, and Hadley S: Invasive fungal infections among organ transplant recipients: results of the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network (TRANSNET). Clin Infect Dis 2012; 50: pp. 1101-1111

PMID:20218876 (PubMed abstract)

- Naik KR, Saroja AO, Doshi DK. Hospital-based Retrospective Study of Cryptococcal Meningitis in a Large Cohort from India. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2017 Jul-Sep; 20(3): 225–228.

PMID:28904453 (PubMed abstract)

- Keane JR. Internuclear ophthalmoplegia: unusual causes in 114 of 410 patients. Arch Neurol. 2005 May;62(5):714-7.

PMID:15883257 (PubMed abstract)

- Mohan S, Ahmed SI, Alao OA, Schliep TC. A case of AIDS associated cryptococcal meningitis with multiple cranial nerve neuropathies. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2006 Sep;108(6):610-3. Epub 2006 Feb 17.

PMID:16487652 (PubMed abstract)

- Sung JY, Cheng PN, Lai KN. Internuclear ophthalmoplegia in cryptococcal meningitis. J Trop Med Hyg. 1991 Apr;94(2):116-7.

PMID:2023288 (PubMed abstract)

- Graybill JR, Sobel J, Saag M, van Der Horst C, Powderly W, Cloud G, Riser L, Hamill R, Dismukes W. Diagnosis and management of increased intracranial pressure in patients with AIDS and cryptococcal meningitis. The NIAID Mycoses Study Group and AIDS Cooperative Treatment Groups. Clin Infect Dis. 2000 Jan;30(1):47-54

PMID:10619732 (PubMed abstract)

- Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2010; 50:291–322.

PMID:20047480 (PubMed abstract)

- Dromer F, Bernede-Bauduin C, Guillemot D, and Lortholary O. Major role for amphotericin B-flucytosine combination in severe cryptococcosis. PLoS ONE 2008; 3: pp. E2870.

PMID:18682846 (PubMed abstract)

- Day J, Chau TT, and Wolbers M. Combination antifungal therapy for cryptococcal meningitis. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: pp. 1291-1302.

PMID:23550668 (PubMed abstract)

- Notes

ID week Fellows' Day 2019 - oral presentation

This case was contributed by:

Parra-Rodriguez L (1), Tanabe M (1), Rezai K (2).

(1) Department of Medicine, John H. Stroger Jr., Hospital of Cook County, Chicago, Illinois.

(2) Division of Infectious Diseases, John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital of Cook County, Chicago, Illinois.

The case was originally presented at ID Week 2019, a joint effort of Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), HIV Medical Association, Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS), and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), during an interactive session on Fellows' Day. Copyright Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA), 2019. Used with permission.

- Citation

- If you refer to this case in a publication, presentation, or teaching resource, we recommend you use the following citation, in addition to citing all specific contributors noted in the case:

Case #19010: A man with a kidney transplant presents with subacute diplopia [Internet]. Partners Infectious Disease Images. Available from: http://www.idimages.org/idreview/case/caseid=581

- Other Resources

-

Healthcare professionals are advised to seek other sources of medical information in addition to this site when making individual patient care decisions, as this site is unable to provide information which can fully address the medical issues of all individuals.

|

|