|

Asymptomatic nodular swelling of the right foot |

- History of Present Illness

- A female from Haiti in her forties with no significant past medical history presented complaining of progressive swelling of her right foot over 10 years. She was seen by multiple physicians in the past and received multiple antibiotics with no improvement. She denied any pain, fever, drainage, difficulty in weight bearing, or similar swelling in other regions of her body. She denied any history of trauma, past surgeries or any known foreign body penetration. Her new primary care physician referred her to an infectious diseases clinic.

- Epidemiological History

- Patient immigrated to the United States from Haiti about five years ago. She reported prior visits to Florida. She denied any smoking, alcohol, or other drug use.

- Physical Examination

The patient was awake and alert in no apparent distress. Her temperature was 98.0°F (36.7°C), pulse 95 beats per minute, blood pressure 149/90 mm Hg, respirations 17 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation 98% on room air. Physical examination revealed a 12 x 7 cm swelling with exophytic nodules on the dorsal surface of the right foot (Fig. 1). There was no erythema, no rash, no draining sinuses, and no discharge appreciated. No evidence of venous stasis or varicose veins was present and no skin ulcers were observed. The skin was dry and intact. On palpation, there was no tenderness and no inguinal lymphadenopathy. The swelling was non-fluctuant and the nodules appeared firm. Full range of motion was appreciated in all digits and peripheral pulses were palpable bilaterally. The remainder of the exam was normal.

- Figure 1: Photograph of right foot showing 12cm x 7cm swelling with exophytic nodules

- Studies

Laboratory studies showed a white blood cell count: 5.7 (normal range: 4.5-11 x109/L), differential included neutrophil: 50% (normal range: 40-80%), lymphocyte: 38.9% (normal range: 20-40%), monocyte: 7.7% (normal range: 2-10%), eosinophil: 2.8% (normal range: 1-6%), basophil: 0.3% (normal range: <2%). Hematocrit and electrolytes were within normal limits. Blood cultures upon admission were negative including for anaerobic organisms and acid-fast bacilli. HIV testing was negative.

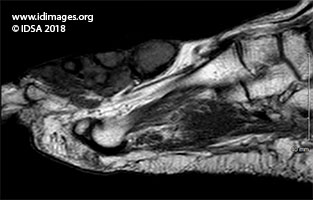

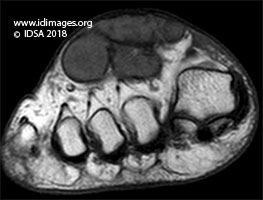

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of her foot revealed a space-occupying lesion within the skin and subcutaneous fat, along the dorsum of the foot overlying the metatarsals and phalanges. Several hyper-intense, rim-enhancing conglomerate lesions were noted with a “targetoid” appearance on the post-contrast images (Fig. 2). The mass extended circumferentially around the first digit phalanges and within the web space of the first/second digit with a maximal thickness of 2.6 cm (Fig. 3).

- Figure 2: MRI of the right foot. Space-occupying lesion evident within the skin and subcutaneous fat along the dorsum of the foot overlying the metatarsals and phalanges. There were several hyper-intense, rim-enhancing conglomerate lesions noted, with a “targetoid” appearance seen post-contrast.

- Figure 3: MRI of the right foot. The mass extended circumferentially around the first digit phalanges and within the web space of the first/second digit. The maximal thickness was 2.6cm.

- Clinical Course Prior to Diagnosis

- The patient underwent a punch biopsy. During the procedure, small yellow granules were seen draining from biopsy site (Fig. 4). Subsequently, the patient underwent excision of the right foot mass with application of wound vacuum-assisted closure (Fig. 5). The excised tissue (Fig. 6) was sent for histopathology and cultures.

- Figure 4: Small granules (arrow) were seen draining from the right foot lesion during the punch biopsy

- Figure 5: Photograph of right foot taken during the surgical resection

- Figure 6: 5 cm x 3 cm, soft excised mass with cystic nodules and yellow granules within

- Diagnostic Procedure(s) and Result(s)

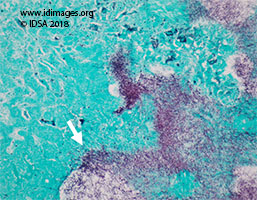

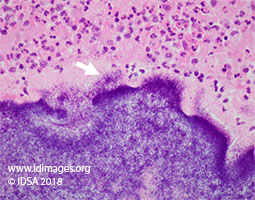

Gram stain (Fig. 7) of biopsy specimen revealed gram-positive, filamentous bacteria, non-acid fast, morphologically consistent with Actinomyces. Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed tangled mass of filaments (Figure 8). Periodic Acid Schiff and Methenamine Silver stains were negative for fungal forms. Cultures failed to grow Actinomyces species. Polymerase chain reaction test was not sent.

- Figure 7: Gram stain of the tissue biopsy showing gram-positive, filamentous bacteria (arrow). Magnification (x40).

- Figure 8: Hematoxylin and eosin staining of granules, showing tangled masses of filaments (arrow). Magnification (x10).

- Treatment and Followup

- After surgical excision of the lesion, patient was started on Intravenous ceftriaxone. She was discharged to complete four - six weeks of intravenous therapy and possible transition to oral antibiotics therapy.

- Discussion

Mycetoma is a slow growing indolent granulomatous infection either due to fungal infection called eumycetoma or bacteria called actinomycetoma. Actinomycetoma can be secondary to Streptomyces somaliensis, Actinomadura madurae, Actinomadura pelletieri, Nocardia brasilliensis and Nocardia asteroides [1]. This process is generally initiated by inoculation of the organism into the subcutaneous tissue. Actinomycetoma typically presents as a slowly progressive enlarging mass which tends to remain localized [2]. These subcutaneous nodules contain suppurative granulomas which may develop into multiple abscesses and sinus tracts. Actinomyces spp. is a rare cause of actinomycetoma [3]. Actinomyces are gram positive non-acid fast, filamentous branched bacteria which require strict anaerobic environment to grow in culture.

The lesion consists of yellow sulfur granules and a tangle of mycelial fragments which are hallmarks of this disease [4]. There granules can be seen draining through sinus tracts or during aspiration or incision [5]. Many actinomycetoma cases are overlooked or misdiagnosed. Tissue sampling is critical for histopathology and culture. Histopathological examination may reveal branching, filamentous bacteria on Gram or silver stain [6].

Actinomycetoma due to Actinomyces spp. is often treated with intravenous ampicillin or penicillin [7] but alternatives such as doxycycline, ceftriaxone and clindamycin have also proven efficacious [8]. For more complicated cases, with extensive abscesses or persisting sinus tracts, surgical excision should be considered [9]. For localized lesions, surgical resection is always preferred in combination with medical management [10].

Mycetoma secondary to Nocardia spp. presents a clinical picture nearly identical to those secondary to Actinomyces spp., which makes it a challenging differential. In fact, on gram stain they are indistinguishable though Nocardia spp. are modified acid-fast positive whereas Actinomyces spp are not. Nocardia spp. tends to grow in aerobic conditions whereas Actinomyces spp. prefers an anaerobic environment [11]. Actinomycetoma must also be differentiated from eumycetoma, a fungal infection most commonly manifested in the foot. The clinical presentations are similar but on histological examination, silver staining may reveal hyphae or other fungal elements in eumycetoma. The filaments of Actinomyces spp. are much narrower than fungal hyphae [12,13]. Botryomycosis, also known as bacterial pseudomycosis is a chronic suppurative infection characterized by a granulomatous inflammatory response to bacterial pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus. These bacterial clusters may be occasionally mistaken for Actinomyces granules, but the former is non-branching, while the latter is branching [14,15]. The clinical and radiological findings of actinomycetoma overlap with benign and malignant neoplasms of soft tissue therefore aspiration or excisional biopsy for culture and histopathology is required to exclude non-infectious causes.

- Final Diagnosis

- Actinomycetoma

- References

-

- van de Sande WWJ (2013) Global Burden of Human Mycetoma: A Systematic Review and

Meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7(11): e2550. doi:10.1371/ journal.pntd.0002550

PMID:24244780 (PubMed abstract)

- Relhan V, Mahajan K, Agarwal P, Garg VK. Mycetoma: An Update. Indian J Dermatol . 2017;62(4):332-340.

PMID:28794542 (PubMed abstract)

- Hogade S, Metgud SC, Swoorooparani. Actinomycetes mycetoma. J Lab Physicians .

2011;3(1):43-5.

PMID:21701663 (PubMed abstract)

- Bowden GHW. Actinomyces, Propionibacterium propionicus, and Streptomyces. In: Baron S,

editor. Medical Microbiology. 4th edition. Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at

Galveston; 1996. Chapter 34. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK8385/

- Sharma S, Valentino III DJ. Actinomycosis. [Updated 2018 Dec 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet].

Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-.Available from:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482151/

- Valour F, Sénéchal A, Dupieux C, et al. Actinomycosis: etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infect Drug Resist . 2014;7:183-97. Published 2014 Jul 5. doi:10.2147/IDR.S39601

PMID:25045274 (PubMed abstract)

- Gilbert DN, Moellering RC Jr, Sande MA. The Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy. Antimicrobial Therapy, Inc 2001; 31:70.

- Smego RA Jr, Foglia G. Actinomycosis. Clin Infect Dis 1998; 26:1255.

PMID:9636842 (PubMed abstract)

- Volante M, Contucci AM, Fantoni M, Ricci R, Galli J. Cervicofacial actinomycosis: still a difficult differential diagnosis. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2005;25:116-119.

PMID:16116835 (PubMed abstract)

- Suleiman SH, Wadaella ES, Fahal AH. The Surgical Treatment of Mycetoma. Wanke B, ed. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2016;10(6):e0004690. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004690

PMID:27336736 (PubMed abstract)

- Shariff M, Gunasekaran J. Pulmonary Nocardiosis: Review of Cases and an Update. Can Respir J . 2016;2016:7494202.

PMID:27445562 (PubMed abstract)

- Cortez KJ, Roilides E, Quiroz-Telles F, et al. Infections caused by Scedosporium spp. Clin Microbiol Rev . 2008;21(1):157-97.

PMID:18202441 (PubMed abstract)

- Guarner J, Brandt ME. Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev . 2011;24(2):247-80.

PMID:21482725 (PubMed abstract)

- Timmermans WM, van Laar JA, van Hagen PM, van Zelm MC. Immunopathogenesis of granulomas in chronic autoinflammatory diseases. Clin Transl Immunology . 2016;5(12):e118. Published 2016 Dec 16. doi:10.1038/cti.2016.75

PMID:28090320 (PubMed abstract)

- Reichenbach J, Lopatin U, Mahlaoui N, et al. Actinomyces in chronic granulomatous disease: an emerging and unanticipated pathogen. Clin Infect Dis . 2009;49(11):1703-10.

PMID:19874205 (PubMed abstract)

- Notes

ID week Fellows' Day 2018 - oral presentation

This case was contributed by:

Ali Aziz, MD, (1), Marjut Kokkola-Korpela, MD (2); Zachary Hart, DPM (3), and Manal Youssef-Bessler, MD (1)

(1) Internal Medicine, Saint Barnabas Medical Center, Livingston, NJ;

(2) Infectious Disease, Saint Barnabas Medical Center, Livingston, NJ

(3) Surgery, Saint Barnabas Medical Center, Livingston, NJ

The case was originally presented at ID Week 2018, a joint effort of Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), HIV Medical Association, Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS), and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), during an interactive session on Fellows' Day. Copyright Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA), 2018. Used with permission.

Last reviewed: 9 March 2019

- Citation

- If you refer to this case in a publication, presentation, or teaching resource, we recommend you use the following citation, in addition to citing all specific contributors noted in the case:

Case #18013: Asymptomatic nodular swelling of the right foot [Internet]. Partners Infectious Disease Images. Available from: http://www.idimages.org/idreview/case/caseid=569

- Other Resources

-

Healthcare professionals are advised to seek other sources of medical information in addition to this site when making individual patient care decisions, as this site is unable to provide information which can fully address the medical issues of all individuals.

|

|