A vesicular lesion on the patient’s posterior left shoulder was unroofed and the vesicle base was sampled along with vesicular fluid, using a nylon flocked swab. The swab was submitted to the virology laboratory for direct detection of Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV) antigen using fluorescent monoclonal antibodies (DFA= Direct Fluorescent Antibody).

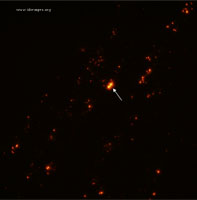

After specimen centrifugation and staining, examination using a fluorescent microscope revealed nuclear and cytoplasmic fluorescence, indicating the presence of VZV antigen (see Figure 2). In addition, VZV IgM and IgG antibody testing was obtained with a positive and negative result respectively, a pattern potentially consistent with primary VZV infection. As lesions were mainly present in sun-exposed areas of the patient’s body, a diagnosis of photolocalized or actinic varicella was made.

- Figure 2. Immunofluorescent stain of varicella zoster virus from a vesicular lesion (60x). Using the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) filter, VZV infected basal and/or parabasal epithelial cells will appear yellow-gold in color (white arrow).

Primary Varicella zoster virus infection, or chicken pox, classically produces a syndrome of fever, malaise and pruritis with an exanthematous rash of maculopapular, vesicular, and papular lesions which erupt in clusters and are present in varying stages at the same time. Varicella most commonly infects unimmunized children and is spread via respiratory route, but with introduction of childhood vaccination, the incidence has fallen [1].

In this case, an adult man presented with lesions consistent with varicella but arising in the same stages simultaneously, after sun exposure. Through skin scrapings and direct fluorescence antibody testing, the diagnosis of photolocalized or actinic varicella was confirmed.

Actinic varicella is a rare presentation of primary varicella zoster virus infection. It has been described only rarely in case reports, more commonly in infants than in adults [2-9]. Initially described as part of a larger category of accentuated viral exanthems in areas of inflammation (such as, diaper areas, feet) [10], it is thought that sun exposure produces a specific unique form of disease. One hypothesis is that exposure to the varicella zoster virus shortly followed by extensive sun exposure allows rapid proliferation of virus into UV-irradiated areas of skin that suffer from local cutaneous inflammation, increased capillary permeability, and the subsequent localized eruptions [11-12]. Other hypotheses suggest that areas of UV exposure are locally immunocompromised which allow for a more severe presentation [13].

In this patient, a particular curiosity was the patient’s age, as well as history later collected that he had been varicella IgG positive previously, although he noted neither primary varicella as a child, nor immunization, leading the team to suspect that this may have been a false positive result. Repeat testing at the time of presentation revealed a negative varicella IgG.

The differential diagnosis at the time of presentation included such concerning diagnoses as smallpox and measles. While smallpox was highly unlikely given lack of occupational exposure or risk of exposure, the question of varicella versus smallpox in this setting with atypical natural history of rash for primary varicella, was very important to differentiate. Hence, the rapid diagnostic of direct fluorescence antibody proved critically important. Regarding measles, the pattern of rash development was not in the classic head down to toe fashion, and the oral lesions did not precede the exanthema nor were they classic Koplik’s spots. He did not have conjunctivitis, coryza, nor cough. The appearance of the rash was not classic either, and the patient had been immunized with MMR.