|

Hypopigmented skin lesions, fevers, chills, sweats and diffuse lymphadenopathy |

- History of Present Illness

A man in his fifties with HIV (current CD4 cell count 57 cells/microliter) presented with several months of generalized malaise, poor appetite, weight loss (13.6 kg, 30 lb). He had also developed scattered hypopigmented patches on his trunk. Over the month prior to evaluation, he developed fevers, chills, sweats, diffuse lymphadenopathy and abdominal bloating.

He had migrated to the United States from South Asia a few weeks prior to presentation having lived in a refugee camp for several decades.

He denied shortness of breath, cough, hemoptysis, vomiting, diarrhea, joint pain or muscle pain. He had no sick contacts but reported numerous insect bites in his country of origin. The common water source at the camp was a well. He has had no other recent travel.

- Past Medical History

He had been diagnosed with HIV about 6 years ago; at that time, his CD4 cell count was 19 cells/microliter. He had been receiving therapy with tenofovir-lamivudine-efavirenz and was virologically suppressed. He was treated for pulmonary tuberculosis several years ago; details of that treatment were unknown.

- Medications

- Tenofovir, lamivudine, efavirenz, trimethroprim-sulfamethoxazole.

- Epidemiological History

He had been married for many years. He had worked as a farmer with exposure to goats and other farm animals. He had never used tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs.

- Physical Examination

The patient was in mild distress. He appeared diaphoretic with increased work of breathing. The blood pressure was 118/71 mmHg, pulse of 88, temperature of 98.7°F (37.1°C), weight of 62.6 kg (138 lb). His examination was notable for extensive tender lymphadenopathy in his posterior and anterior cervical chain, axilla, inguinal canal, and epitrochlear area, measuring 1-2 cm. Cardiopulmonary examination was notable for soft left upper lobe crackles. Abdominal exam was notable for a liver edge palpable 2cm below the costal margin and a palpable spleen tip. His skin exam revealed numerous hypopigmented macules and papules on his face, neck, and trunk (Figure 1a and 1b). The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

- Figure 1a. Image of hypopigmented rash on face

- Figure 1b. Image of hypopigmented rash on trunk

- Studies

The white blood cell count was 1.27 x10³ cells per microliter (reference range, RR, 4-10.4). Absolute neutrophil count was 890 cells per microliter (RR 2200-8850) and total lymphocyte count was 300 cells per microliter (RR 1090-3300). The CD4 count was 57 cells/uL. The HIV RNA level was undetectable. The creatinine was 1.25 mg per dL (RR 0.66-1.25). Liver function tests were notable for AST of 53 U/L (RR 15-46), alkaline phosphatase 284 U/L (RR 38-126) and albumin 2.6 g per dL (RR 3.4-4.9). The chest x-ray revealed areas of scarring and bronchiectasis in the left upper lobe (Figure 2). Three sputum specimens were negative for acid fact bacilli (AFB) by smear; a sputum AFB culture performed 3 months prior had been finalized as no growth.

- Figure 2. Chest X-ray at presentation. Scarring and bronchiectasis seen within the left upper lobe likely secondary to prior tuberculosis infection.

- Clinical Course Prior to Diagnosis

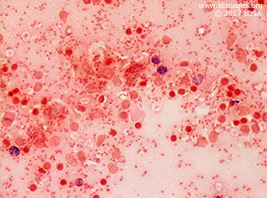

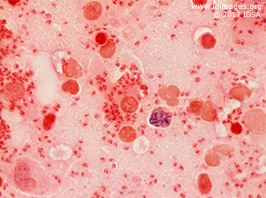

He was referred to otolaryngology for an excisional biopsy of a posterior auricular lymph node (1.5 x 0.9 x 0.5 cm). The gram stain is shown in Figures 3a and 3b.

- Figure 3a. Gram stain of lymph node (50x)

- Figure 3b. Gram stain of lymph node (100x)

- Diagnostic Procedure(s) and Result(s)

Sputum TB PCR was negative. Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial blood cultures were negative.

The posterior auricular excisional lymph node biopsy was sent for pathology as well as bacterial, fungal and mycobacterial cultures. Pathology demonstrated sheets of histiocytes with numerous intracytoplasmic amastigotes. Giemsa stain of touch imprints revealed numerous organisms with kinetoplasts consistent with leishmania amastigotes. Silver stain for fungus was negative. All cultures were negative. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis.

The dermatology team performed a shave biopsy of the rash on his back. The dermis demonstrated granulomas composed of epithelioid histiocytes containing numerous organisms some with identifiable kinetoplasts, consistent with cutaneous leishmaniasis.

A portion of the lymph node was sent to the CDC reference lab for Leishmania PCR. This returned positive for Leishmania donovani which is endemic in his home country in South Asia.

- Treatment and Followup

He was admitted for initiation of IV therapy with liposomal amphotericin B. He was treated with 4mg/kg IV daily on days 1 through 5, then days 10, 17, 24, 31, and 38. The patient responded well to treatment with resolution of his constitutional symptoms. He gained 11 kg (22 lbs). His white blood cell count increased to 2.97 x103 cells per microliter. His absolute neutrophil and lymphocyte count increased to 1700 and 600 per microliter, respectively. His CD4 count increased to 122 cells/microliter at 3 months after presentation. His ART was changed to a fixed dose combination of efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. Because his CD4 count remained below 200 cells/microliter he received prophylactic therapy with infusion of liposomal amphotericin B 5mg/kg IV every 4 weeks.

- Discussion

Leishmaniasis reflects a variety of pathogenic processes caused by different species of the protozoan parasite in the genus of Leishmania. It has a dimorphic lifecycle with an amastigote stage in the sand fly which is transmitted to humans when the insect takes a blood meal. The amastigote is phagocytosed and becomes a promastigote. It survives and is able to multiply intracellularly (2). It develops a kinetoplast as an outpouching of DNA at a right angle to its nucleus which aids in identification. Visceral leishmaniasis (also called Kala-Azar) is widely distributed in Africa, Asia, South and Central America. The reservoir for the organism is small mammals. Visceral leishmaniasis presents with a wide spectrum of disease from mild or asymptomatic infection to fever, weight loss, hepatosplenomegaly, diffuse lymphadenopathy, pancytopenia, and hypergammaglobulinemia. Renal involvement can occur. Immunosuppressed hosts and people with HIV are typically more severely affected. Leishmaniasis is emerging as an under-recognized cause of disease in developing countries. A hypopigmented rash can occur with leishmaniasis which can be macular, papular, or nodular (3). This can manifest even after the completion of treatment when it is called post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis.

Leishmania donovani is endemic in the region of South Asia, where his refugee camp was located (1) and is an emerging pathogen particularly in persons with HIV, with 40% of all cases of Leishmania donovani worldwide occurring there (4).

Laboratory diagnosis consists of identification of the organism in infected tissues including lymph nodes, spleen, liver, and bone marrow (5). PCR-based testing to confirm the diagnosis and to speciate the organism are available at the CDC. Other identification methods include culture and antibody titers.

For the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis, liposomal amphotericin B is the drug of choice in the US (6). In people with HIV, ART should be started immediately. Combination therapy with amphotericin B and miltefosine is an option for refractory cases (6).

Relapse rates are high in HIV-infected patients with low CD4 counts (<200 cells/uL). In an early case series of 78 patients, 100% of patients with AIDS treated for leishmaniasis relapsed after stopping amphotericin B (7). In HIV-infected patients (all CD4 counts), secondary prophylaxis with amphotericin B decreased relapse from 80% to 50% at 12 months (8). In a prospective series of 27 HIV-infected patients with an initial diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis, patients with a CD4 of less than 100 cells/mL were at risk for relapsed disease despite being maintained on secondary prophylaxis while those with a CD4 of more than 200 cells/mL did not experience any relapses (9). Our patient was started on secondary prophylaxis to reduce his risk of recurrence with the plan to continue until his CD4 count was consistently above 200 cells/mL for 3 months.

- Final Diagnosis

Visceral Leishmaniasis by Leishmania donovani

- References

-

- Magill, Alan J. (2015). Leishmania species. In G. M. Mandell, J.E. Bennett, and D. Raphael Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Disease (p3094) Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone.

- CDC - DPDx – Leishmaniasis. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/leishmaniasis/index.html

- Koley S, Mandal RK, Choudhary S, Bandyopadhyay A. Post-kala-azar Dermal Leishmaniasis Developing in Miltefosine-Treated Visceral Leishmaniasis. Indian Journal of Dermatology. 2013;58(3):241.

PMID:3667302 (PubMed abstract)

- Burza S, Mahajan R, Sanz MG, Sunyoto T, Kumar R, Mitra G, Lima MA. HIV and Visceral Leishmaniasis Coinfection in Bihar, India: An Underrecognized and Underdiagnosed Threat Against Elimination. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59 (4): 552-555.

PMID:24814660 (PubMed abstract)

- Sundar S, Rai M. Laboratory Diagnosis of Visceral Leishmaniasis. Clinical and Diagnostic Laboratory Immunology. 2002;9(5):951-958.

PMID:120052 (PubMed abstract)

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Leishmaniasis: Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2017;96(1):24-45.

PMID:5239701 (PubMed abstract)

- Davidson RN. AIDS and leishmaniasis. Genitourinary Medicine. 1997;73(4):237-239.

PMID:1195849 (PubMed abstract)

- López-Vélez R, Videla S, Márquez M, Boix V, Jiménez-Mejías ME, Górgolas M, Arribas JR, Salas A, Laguna F, Sust M, Cañavate C, Alvar J; Spanish HIV-Leishmania Study Group. Amphotericin B lipid complex versus no treatment in the secondary prophylaxis of visceral leishmaniasis in HIV-infected patients. J Antimicrob Chemother 2004; 53 (3): 540-543.

PMID:14739148 (PubMed abstract)

- Bourgeois N, Lachaud L, Reynes J, Rouanet I, Mahamat A, Bastien P., J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008 May 1;48(1):13-9. Long-term monitoring of visceral leishmaniasis in patients with AIDS: relapse risk factors, value of polymerase chain reaction, and potential impact on secondary prophylaxis.

PMID:18300698 (PubMed abstract)

- Notes

ID week Fellows' Day 2017 - poster presentation

This case was contributed by:

James Enser, MD (1) and Cindy Noyes, MD (2)

(1) Infectious Disease, University of Vermont medical center, Burlington, VT;

(2) Infectious Disease, Fletcher Allen Health Care/University of Vermont, Burlington, VT

The case was originally presented at ID Week 2017, a joint effort of Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), HIV Medical Association, Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS), and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), during an interactive session on Fellows' Day.

Copyright Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA), 2017. Used with permission.

Last reviewed: 14 May 2018

- Citation

- If you refer to this case in a publication, presentation, or teaching resource, we recommend you use the following citation, in addition to citing all specific contributors noted in the case:

Case #17021: Hypopigmented skin lesions, fevers, chills, sweats and diffuse lymphadenopathy [Internet]. Partners Infectious Disease Images. Available from: http://www.idimages.org/idreview/case/caseid=552

- Other Resources

-

Healthcare professionals are advised to seek other sources of medical information in addition to this site when making individual patient care decisions, as this site is unable to provide information which can fully address the medical issues of all individuals.

|

|