|

Fevers after an elective intracranial orbital reconstruction and cranioplasty |

- History of Present Illness

A young female toddler with craniosynostosis and sinus hypoplasia underwent an elective intracranial orbital reconstruction and cranioplasty. The patient received surgical antibiotic prophylaxis with cefazolin. The procedure was uncomplicated, apart from an incidental finding of a small dural defect which was repaired. Post-operatively, the patient was continued on cefazolin prophylaxis as per local plastic surgery guidelines.

The patient was febrile up to 39.3°C/102.7°F (rectal) during the first two post-operative days. Blood cultures, urine cultures and a nasopharyngeal aspirate for multiplex respiratory virus PCR were negative. A chest radiograph was also normal. Her incision showed no evidence of surgical site infection. A presumptive diagnosis of central fever due to neurosurgical intervention was made at the time. She was started on antipyretic therapy and antibiotic prophylaxis with cefazolin was continued. The patient subsequently remained afebrile through post-operative days three and four.

On the fifth post-operative day, she developed a new fever of 38.9°C/102.0°F (rectal) and became tachycardic. Over the following two days, the patient remained febrile, became increasingly irritable and lethargic, and remained tachycardic despite administration of several fluid boluses. Two repeat chest radiographs and a plain film of the abdomen, as well as a urine culture and sputum culture were unremarkable over those two days. On the seventh post-operative day, she developed new respiratory distress requiring 3 liters per min of supplemental oxygen. In addition, she had a focal tonic-clonic seizure of her left arm with left gaze deviation.

- Past Medical History

- Asthma

- Medications

At the time of the clinical deterioration, she was receiving prophylactic cefazolin 50 mg/kg/day IV divided every 8 hours (antibiotic day 5).

Immunization History:

Her childhood vaccination was incomplete for age. She was missing both measles-mumps-rubella vaccine doses, the first dose of the varicella vaccine and a diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis-inactivated polio-Haemophilus influenzae type b-hepatitis B booster. She had however received all doses of pneumococcal vaccines.

- Physical Examination

The patient was lethargic, pale and was grunting. The maximal temperature over the previous 24 hours was 40.1°C/104.2°F (rectal). Blood pressure 114/85 mm Hg, heart rate 136 beats per minute, respiratory rate 36 respirations per minute, oxygen saturation 100% on 3 liters per min of supplemental oxygen.

The cranial incision site was non-tender, non-erythematous, without any pus or swelling. The pupils were equal and reactive to light. There was no nuchal rigidity. The tone in both upper and lower limbs was reduced. Tympanic membranes were non-erythematous and non-bulging bilaterally. A mastoid exam was not documented. Auscultation of the lungs showed good equal air entry bilaterally without any adventitious sounds. Cardiovascular exam revealed normal heart sounds, no gallops or murmurs. Capillary refill was less than 2 seconds and skin turgor was normal. The abdomen was soft, non-tender and there was no hepatosplenomegaly. There was no lymphadenopathy. There were no rashes, Janeway lesions or Osler nodes.

- Studies

The white blood cell count was 15 200/µL (normal 6 000-17 000/µL) with an absolute neutrophil count of 12 750/µL (normal 1500-8500/µL). Hemoglobin was 81 g/L (normal 105-135 g/L), down from 106 g/L 2 days prior, and platelets were 265 x 109/L (normal 140-450 x 109/L). The C-reactive protein was 334 mg/L (normal 0-5 mg/L). The patient also had a sodium level of 125 mM (baseline 139 mM; normal 135-145 mM).

A CT head with contrast showed bilateral small frontal hygromas which were expected postoperative changes, without evidence of empyema or other acute intracranial pathology.

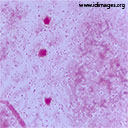

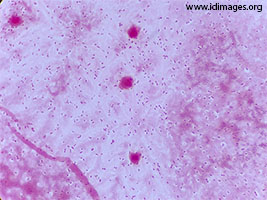

In the context of persistent fever, new-onset vomiting, lethargy and a recent intracranial surgery, a lumbar puncture was performed to rule out meningitis. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was clear. CSF analysis revealed a white blood cell count of 35/µL (normal 0-5/µL), with 50% monocytes and 44% neutrophils, 0 erythrocytes, protein of 1.2 g/L (normal 0.15-0.45 g/L) and a glucose of 0 mM (2.4 – 4.4 mM). CSF gram stain is shown in Figure 1.

- Figure 1. CSF gram stain

- Diagnostic Procedure(s) and Result(s)

A blood culture obtained on the seventh post-operative day was positive for gram positive cocci in chains. After the lumbar puncture was performed, the patient was started on ceftriaxone and vancomycin at meningitic dosing to provide coverage for the most common bacteria causing meningitis in this age group, namely Streptococcus pneumoniae (including ceftriaxone-resistant strains) and Neisseria meningitidis. Corticosteroids were not administered empirically. CSF gram stain showed 4+ gram-positive diplococci. Cultures of blood and CSF grew penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae, confirming the diagnosis of healthcare-associated pneumococcal meningitis. The organism’s antibiogram with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) obtained by E-test for penicillin, ceftriaxone and meropenem are shown in Table 1. As susceptibility testing confirmed ceftriaxone sensitivity, vancomycin was discontinued, and the patient was kept on ceftriaxone.

|

Antibiotic

|

Sensitivity

|

MIC (mg/L)

|

|

Penicillin (meningitic)a

|

R

|

1

|

|

Penicillin (non-meningitic)b

|

R

|

1

|

|

Ceftriaxone (meningitic)a

|

S

|

0.25

|

|

Ceftriaxone (non-meningitic)b

|

S

|

0.25

|

|

Meropenem

|

S

|

0.25

|

|

Clindamycin

|

R

|

|

|

Erythromycin

|

R

|

|

Moxifloxacin

|

S

|

|

Tetracycline

|

R

|

|

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole

|

S

|

Table 1. CSF bacterial culture: Streptococcus pneumoniae antibiogram

a: using reference MIC susceptibility breakpoints for Streptococcus pneumoniae causing meningitis

b: using reference MIC susceptibility breakpoints for Streptococcus pneumoniae causing non-meningeal infections

- Treatment and Followup

Unfortunately, after 3 days of ceftriaxone, the patient spiked a new fever, was still lethargic and developed abnormal right-sided upper and lower extremity movements. A head MRI was ordered to rule-out an intracranial collection, and ceftriaxone was changed to meropenem to cover possible nosocomial multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacilli causing a superimposed central nervous system (CNS) infection. The MRI showed lesions suggestive of either small vessel vasculitis secondary to bacterial meningitis – a rare complication – or central pontine myelinolysis due to rapid correction of hyponatremia documented a few days prior. Given the absence of a new focus of infection, meropenem was discontinued and ceftriaxone was restarted. In addition, given the uncertain etiology of the cerebral lesions, the patient received a 10-day course of intravenous corticosteroids and one dose of intravenous immunoglobulins as treatment of cerebral small vessel vasculitis.

A repeat lumbar puncture performed after 11 days of antibiotics to document CSF sterility revealed normal CSF parameters and a negative CSF bacterial culture. The patient subsequently developed post-infectious hydrocephalus for which a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt was inserted. She received a total of 21 days of appropriate antibiotic therapy (adequately covering penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae at meningitic doses). The treatment duration was prolonged in her case pending repeat head imaging which showed no intracranial abscesses and the placement of a VP shunt.

The patient’s infection resolved but she had neurologic sequelae that are improving.

- Discussion

The incidence of community-acquired bacterial meningitis in high-income countries is estimated at 1 to 3 cases per 100,000 individuals, all ages included (1, 2). However, the incidence in young children is significantly higher, ranging from 2 to 80 cases per 100,000 individuals depending on the age group (1). Specifically, pneumococcal meningitis has a worldwide incidence of about 17 cases per 100,000 individuals in children less than 5 years of age (1, 3). As for healthcare-associated bacterial meningitis, incidence rates are derived from neurosurgical patient populations and range between 0.5% and 8% (4). Given that bacterial meningitis tends to affect young children and that the signs and symptoms are non-specific in this age group, a high index of suspicion is required to make the diagnosis.

Causal organisms also vary according to age. Children younger than 6 weeks are at increased risk of meningitis due to pathogens present in the maternal genitourinary flora such as Streptococcus agalactiae and Enterobacteriaceae, whereas Streptococcus pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitidis predominate in children older than 6 weeks. Overall, the most common pathogen in children less than 5 years of age is S. pneumoniae (5). This epidemiological data helps to inform appropriate empiric antimicrobial treatment choices when faced with a suspected case of bacterial meningitis.

Prompt initiation of appropriate antibiotic therapy is the cornerstone of treatment for bacterial meningitis. Empiric antibiotics are chosen according the usual antibiotic susceptibility patterns of the most likely pathogens. In the context of bacterial meningitis, the MIC of key antibiotics must be determined to inform specific therapy. The MIC is defined as the concentration of antibiotic at which growth of 90% of isolates is inhibited. (6). An additional challenge for CNS infections is that the concentration of antibiotic in the CSF is much lower than in the serum due to the blood brain barrier (BBB). As such, in order to achieve therapeutic concentrations of antibiotics in the CSF, a higher concentration of antibiotic must be administered in the blood stream. MIC breakpoints are therefore lower when the isolate is grown in the CSF as compared to non-meningeal sites as illustrated in the table presented in this case.

Global surveillance of pneumococcal susceptibility patterns has shown that rates of penicillin non-susceptibility have been increasing over the past 30 years worldwide (6). Whereas penicillin was frequently part of empiric antibiotic regimens for bacterial meningitis in the past, the increasing incidence of penicillin non-susceptible S. pneumoniae has led to its replacement by third generation cephalosporins. Third generation cephalosporins have adequate CSF penetration and good activity against the usual pathogens causing bacterial meningitis, including S. pneumoniae. However, there has also been a trend towards increasing cephalosporin resistance in pneumococcal isolates worldwide (7). Although the absolute rates of resistance remain low (8), the dramatic outcomes associated with inappropriately treated meningitis have led to recommending the addition of vancomycin in the empiric regimen of bacterial meningitis in certain guidelines (9, 10). Ultimately, the decision to add vancomycin should be guided by local antimicrobial resistance patterns (12).

Corticosteroids also play a role in the treatment of bacterial meningitis. Current evidence suggests that adjunctive dexamethasone reduces rates of hearing impairment in H. influenzae type b (Hib) meningitis in children. Its benefit in pediatric pneumococcal meningitis, however, is less clear and experts vary in recommending its use. In addition, beneficial effects of adjunctive corticosteroids have not been observed in low-income countries (13). Moreover, corticosteroids have no benefit in meningitis caused by other organisms and are not recommended in the context of healthcare-associated meningitis (13).

The advent of vaccination against several causal pathogens of bacterial meningitis has significantly contributed to the reduction of mortality and morbidity related to both community-acquired and nosocomial bacterial meningitis over the last decades (1, 14, 15). Furthermore, several routine practices such as hand-hygiene (16) and perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis (17) have been shown to further help prevent nosocomial meningitis. Despite all these efforts, the fatality rate has remained virtually unchanged at around 14% (1).

In cases where prevention fails, prompt initiation of appropriate empiric antimicrobial treatment guided by local epidemiological data and susceptibility patterns is essential to prevent mortality and morbidity. As illustrated by the case described here, even non-lethal cases can be quite devastating.

- Final Diagnosis

- Pneumococcal meningitis post-intracranial surgery

- References

-

- Thigpen MC, Whitney CG, Messonnier NE, Zell ER, Lynfield R, Hadler JL, et al. Bacterial Meningitis in the United States, 1998–2007. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364(21):2016-25.

PMID:21612470 (PubMed abstract)

- Agrawal S, Nadel S. Acute bacterial meningitis in infants and children: epidemiology and management. Paediatric drugs. 2011;13(6):385-400.

PMID:21999651 (PubMed abstract)

- Tin Tin Htar M, Madhava H, Balmer P, Christopoulou D, Menegas D, Bonnet E. A Review of the Impact of Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Conjugate Vaccine (7-valent) on Pneumococcal Meningitis. Advances in Therapy. 2013;30(8):748-62.

PMID:24000099 (PubMed abstract)

- van de Beek D, Drake JM, Tunkel AR. Nosocomial Bacterial Meningitis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362(2):146-54.

PMID:20071704 (PubMed abstract)

- Janowski AB, Newland JG. From the microbiome to the central nervous system, an update on the epidemiology and pathogenesis of bacterial meningitis in childhood. F1000Research. 2017;6(86):1-11.

PMID:28184287 (PubMed abstract)

- Liñares J, Ardanuy C, Pallares R, Fenoll A. Changes in antimicrobial resistance, serotypes and genotypes in Streptococcus pneumoniae over a 30-year period. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2010;16(5):402-10.

PMID:20132251 (PubMed abstract)

- Ktari S, Jmal I, Mroua M, Maalej S, Ben Ayed NE, Mnif B, et al. Serotype distribution and antibiotic susceptibility of Streptococcus pneumoniae strains in the south of Tunisia: A five-year study (2012-2016) of pediatric and adult populations. International journal of infectious diseases : IJID : official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases. 2017;65:110-5.

PMID:29111412 (PubMed abstract)

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System - Report 2015. Series. http://publications.gc.ca/pub?id=9.512584&sl=0: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2015. Report No.: 2369-0712.

- Le Saux N, Canadian Paediatric Society ID, Immunization C. Guidelines for the management of suspected and confirmed bacterial meningitis in Canadian children older than one month of age. Paediatrics & Child Health. 2014;19(3):141-6.

- van de Beek D, Cabellos C, Dzupova O, Esposito S, Klein M, Kloek AT, et al. ESCMID guideline: diagnosis and treatment of acute bacterial meningitis. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2016;22:S37-S62.

PMID:27062097 (PubMed abstract)

- Sullins AK, Abdel-Rahman SM. Pharmacokinetics of Antibacterial Agents in the CSF of Children and Adolescents. Pediatric Drugs. 2013;15(2):93-117.

PMID:23529866 (PubMed abstract)

- van de Beek D, Brouwer M, Hasbun R, Koedel U, Whitney CG, Wijdicks E. Community-acquired bacterial meningitis. Nature reviews Disease primers. 2016;2:16074.

PMID:27808261 (PubMed abstract)

- Hedberg AL, Pauksens K, Enblad P, Soderberg J, Johansson B, Kayhty H, et al. Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination administered early after neurotrauma or neurosurgery. Vaccine. 2017;35(6):909-15.

PMID:28069358 (PubMed abstract)

- Marom T, Bookstein Peretz S, Schwartz O, Goldfarb A, Oron Y, Tamir SO. Impact of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccines on Selected Head and Neck Infections in Hospitalized Israeli Children. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2017;36(3):314-8.

PMID:27879558 (PubMed abstract)

- Le TA, Dibley MJ, Vo VN, Archibald L, Jarvis WR, Sohn AH. Reduction in surgical site infections in neurosurgical patients associated with a bedside hand hygiene program in Vietnam. Infection control and hospital epidemiology. 2007;28(5):583-8.

PMID:17464919 (PubMed abstract)

- Li Z, Wu X, Yu J, Wu X, Du Z, Sun Y, et al. Empirical Combination Antibiotic Therapy Improves the Outcome of Nosocomial Meningitis or Ventriculitis in Neuro-Critical Care Unit Patients. Surgical infections. 2016;17(4):465-72.

PMID:27104369 (PubMed abstract)

- Notes

This case was contributed by:

Assil Abda (1), Marie-Astrid Lefebvre M.D.(2,3)

(1) Undergraduate Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, (2) Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Department of Pediatrics, The Montreal Children's Hospital of the McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, QC, Canada. (3) Faculty of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, McGill University, Montreal QC, Canada.

This case was originally submitted to the Clinical Case Challenge on Diagnostics and Antimicrobial Resistance 2018 organized by the London School of Health and Tropical Medicine's International Diagnostics Centre and partners. Copyright Partners ID Images, 2018. Used with permission.

Last reviewed: 14 October 2018

- Citation

- If you refer to this case in a publication, presentation, or teaching resource, we recommend you use the following citation, in addition to citing all specific contributors noted in the case:

Case #18017: Fevers after an elective intracranial orbital reconstruction and cranioplasty [Internet]. Partners Infectious Disease Images. Available from: http://www.idimages.org/idreview/case/caseid=559

- Other Resources

-

Healthcare professionals are advised to seek other sources of medical information in addition to this site when making individual patient care decisions, as this site is unable to provide information which can fully address the medical issues of all individuals.

|

|